|

Technical vs political: Capacity development at times focuses more on provision of resources, skills/knowledge, and organization targets rather than politics, power, and incentives. The former targets are more amenable to being addressed through methods under a high degree of control of outsiders. They can provide resources, do training, provide technical assistance, develop management systems, and support service delivery relatively easily. The focus on political issues which are equally important but harder to address is often left out or ignored.

- External actors and local capacity: Fragile states often need external actors to fill a national security deficit and lay the foundation for peace and restoration of law and order. However, another gap that poses difficulties for external assistance concerns an absence of capacity to manage public resources, which can lead to problems with corruption and accountability.

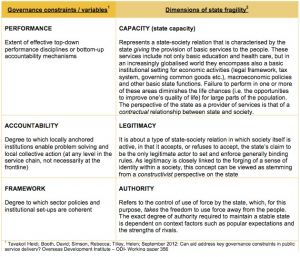

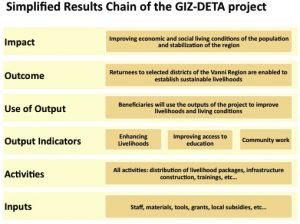

Given these dilemmas the context analysis is important prior to undertaking any capacity development measures. In order to better target the capacity development measures, two recent studies provide a very useful framework for assessing the capacity development measures relative to context needs. These basic concepts have also been taken up in new BMZ Strategy Paper 4/2013 on Development for Peace and Security (pages 8-9) and also in the 6/2013 BMZ Strategy on Transitional Development Assistance (page 9).

Table 1: Elements of governance constarints and dimensions of state fragility

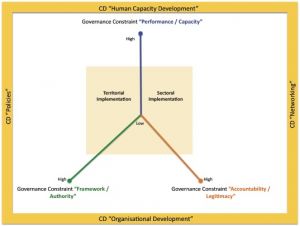

Figure 1: Governance constraints / fragility dimensions in relationship to the four GIZ dimensions of capacity development

A key capacity development strategy of the GIZ-DETA project was:

- The project works with and through the government institutions to achieve the project objectives and improving the efficiency of the service delivery of the government institutions (the government provides all services to the final beneficiaries)

- Capacity development will be undertaken mostly through on-the-job training and advisory services directly to the government service providers who then in-turn provide capacity development to the beneficiaries

- A key instrument / tool for achieving capacity development and undertaking on-the-job training is the local subsidy contract instrument of the GIZ

The following example illustrates how the GIZ-DETA project in Sri Lanka contributed towards achieving the defined strategy.

Photo 1: Meeting with partner institutions - police department- (source: GIZ-DETA)

Context

With the end of the civil conflict in Sri Lanka in May 2009 decades of turmoil that seriously constrained the country’s economic development and that negatively impact on people’s lives, especially those living in the North and East of the country finally ended. The decades long conflict and in particular the intense fighting of the final stages led to extensive destruction of the socio-economic and production infrastructure as well as weakened public administration system in the North and East. Equally important has been the negative effects that the turmoil has had on psychological well-being and livelihoods of the people. Not helpful in the whole process has also been the regular shifts in the administrations between government, warring factions as well as the military during the conflict period as this has considerably affected the capabilities of the administrators as well as the populations perception of the state (related to performance/capacity and accountability/legitimacy constraints).

Nevertheless considerable progress has been made towards the commitment by the Government of Sri Lanka to find a durable solution for all people displaced by the war, including return to their home areas. Since the humanitarian crisis triggered the displacement of nearly 300,000 Persons from the conflict zone in 2008 and into 2009, the Government ensured basic humanitarian assistance to those in camps, supported by the United Nations (UN), national and international Non-Government Organizations (NGOs), and International Organizations (IOs). Soon after the conflict ended, the Government launched a sustained resettlement campaign for the displaced, beginning with the 180-Day Programme in mid-2009, engaging closely with partners in rapid early recovery interventions to stabilize returning communities. Building upon these achievements, a Presidential Task Force has been appointed to formulate a strategic framework for revitalization of the province. The Uthuru Wasanthaya’ (Northern Spring), a medium term development strategy for 2010 – 2012 programme was launched, which serves as master plan for resettlement and development of the Northern Province (related to framework/authority constraints).

Photo 2: Benefiacry selection (source: GIZ-DETA)

Key areas of intervention were defined as: restoration of socioeconomic and personal stability and safety; revitalization of basic livelihoods; development of infrastructure in roads, electricity, ports, transport, water supply and sanitation and housing; improvement of the rural economy through technological transformation in the agricultural and livestock sectors, fishing and valuable mineral resource; improvement of vocational education; implementation of institutional reform for upgrading the quality and performance of the public service and its overall responsiveness to the needs and concerns of the public; establishment of industrial estates and economic centres.

The programme is modelled on the initial Negenahira Navodaya (Eastern Awakening) that was designed as an accelerated three-year project for restoring normalcy in the Eastern province soon after the end of the war. Both projects are incorporated in the ‘Mahinda Chintana’ – A Ten Year Horizon Development Framework 2006-2016 for Sri Lanka (related to framework/authority constraints). The projects are directly supervised by President’s office and the Ministry of Nation Building and Estate Infrastructure Development, while in the formulation of regional strategies a key role should be taken by the local authorities (e.g. provincial council), the relevant District Secretaries and a wide spectrum of grass-root level communities in the province. The projects are financially supported by the state authorities at the national level, including the Department of National Planning, Ministry of Plan Implementation, Ministry of Highways, Department of External Resources, Department of Census and Statistics, Central Bank, Peace Secretariat, and international non-government organizations like Consortium of Humanitarian Agencies (CHA), and United Nations (UN).

A Joint Plan of Assistance for the Northern Province (JPA) was developed through a consultative process led by the Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) through the Presidential Task Force (PTF) on assistance needed to meet the returnees’ immediate needs for shelter, food, health, nutrition and education, while working to restore basic services, infrastructure and livelihoods. Upon the Government’s invitation this process was undertaken jointly with the United Nations and its agencies (UN), national and international Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and International Organizations (IOs). One main objective under the Joint Plan of Assistance for the Northern Province (JPA) is to support the civilian administrations of the Northern Province to further their capacity for providing administrative services to returnees, related to access to land, missing documentation, family reunification, protection of women and children, SGBV, services for elderly and disabled individuals, among others (related to performance/capacity and to a limited accountability/legitimacy constraints). This particular support will be led by respective government authorities at every level in the districts.

Some of the key issues to be supported by the administration include facilitating access to land, addressing issues related to missing documentation, supporting family reunification, providing protection of women and children, supporting addressing sexual and gender based violence, provision of services for elderly and disabled individuals. For each of these specialised services the respective government authorities at every level in the districts was responsible for leading and managing the processes. Apart from the government effort, a resource and personnel intensive support was provided by bilateral and multilateral donor organisations who pursued different approaches for implementing the programmes, ranging from direct support to the government hiring of international, national and local non-governmental organisations or private sector organisations who implemented projects on behalf of the donor organisations (related to framework/authority and performance/capacity constraints).

This does not mean, however, that there is no internal displacement in the country anymore. As of the end of September 2012, more than 115,000 internally displaced people (IDPs) were still living in camps, with host communities or in transit sites, or had been relocated, often against their will, to areas other than their places of origin. Among those registered as having returned, many have not been able to achieve a durable solution but continue to face difficulties in accessing basic necessities such as shelter, food, water and sanitation, in rebuilding their livelihoods, and in exercising their civil rights. De-mining operations are still ongoing in livelihood areas. Unresolved land issues have been a major obstacle to durable solutions for IDPs and IDP returnees. Conflict-affected areas remain highly militarised, which has made progress towards achieving durable solutions more difficult. The military has become an important economic player and a key competitor of local people including returnees in the areas of agriculture, fishing, trade, and tourism. It has also been involved in areas that would normally come under civilian administration. It continues to occupy private land, thereby impeding IDPs’ return. The Government of Sri Lanka has also developed a very sceptical perception of both international and national non-governmental organisations as well various different donor organisations, largely as a result of their viewpoints during and in the post-conflict period (related to accountability/legitimacy and framework/authority constraints).

Photo 3: Distribution of fishing to recent resettled IDPs (source: GIZ-DETA)

A core strategy of the GIZ supported ‘Development Oriented Emergency and Transitional Aid’ (DETA) project in Northern Sri Lanka has been to support the government of Sri Lanka in strengthening the administration in the Northern province of Sri Lanka. In particular strenthening the service provision capacities required for both the returning IDPs as well as for the existing communities. This was not only necessary to improve the efficiency of the service provision but also essential in re-establishing the trust and confidence between the state and society in the Northern Province of Sri Lanka.

- The project follows a participatory approach while at the same time it works through relevant government institutions, taking into account the ‘do no harm’ principle. National and regional state authorities implement the activities, also to support the acceptance of Sri Lankan government institutions in the region. Livelihood support measures are based on needs of households and communities and put into reality through existing mechanisms such as farmers’ associations, rural development societies and the private sector. The project promotes the interaction of not only state and the public but also the effective and efficient service delivery by state institutions.

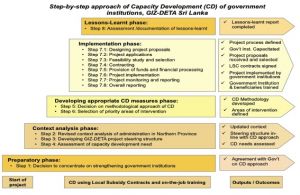

Step-by-step implementation of capacity development

Step 1: Decision to concentrate on strengthening the government structure

The results of the initial context analysis for the proposed GIZ-DETA in Northern Sri Lanka led to the proposal that the project should work through a national non-governmental organisation as part of the implementation process. The methodological approach foresaw that the GIZ-DETA project would contract most of the implementation work to a national NGO who would then coordinate their activities with the Provincial Council and the government line departments, but the actual implementation would be undertaken by and through the national NGO. One of the reasons for the proposal was also the very restrictive access given to international organisations at the time and the fact that national NGOs access to areas in the North was slightly better. The approach of contracting a national NGO seemed appropriate at the conceptual stage of the project. However, with the rapidly changing framework conditions a change in methodological approach was deemed necessary.

GIZ-DETA project started officially in September 2010 and several important events led to a change in the methodological approach of the project:

- In August 2010 the Government of Sri Lankan moved the DETA project from the Ministry of Nation Building and Estate Infrastructure Development to the newly created Ministry of Economic Development (MED).

- In 2009, the government of Sri Lanka created the Presidential Task Force (PTF), whose task it is to coordinate all reconstruction and development in the North. PTF also coordinates activities of the security agencies of the Government in support of resettlement, rehabilitation and development and to liaise with all organizations in the public and private sectors and civil society organizations for the proper implementation of programs and projects. Since June of 2010 the NGO Secretariat is responsible for approving the plans for development projects. It was therefore necessary for GIZ-DETA to get approval from the new PTF / NGO Secretariat to operate in the Northern province.

- The project commission offer was translated from German to English and was formally submitted to the PTF / NGO Secretariat. The PTF / NGO Secretariat raised serious objections to the proposed methodological approach of the project of working through a national NGO (in addition to objections regarding the project component on psycho-social interventions). The PTF / NGO Secretariat indicated that they would only allow the project to work with and through the existing government structure of line departments and provincial council system.

- With the arrival of the GIZ international expert responsible for the project commission a reassessment of the project methodological approach was undertaken. The revised context assessment indicated that the implementation of the project with and through the government line departments as required by the PTF / NGO Secretariat was both possible and also desirable,

- The former North-Eastern province was sub-divided into two provinces in 2007, namely a Northern and Eastern province. In 2009 a Governor was appointed for the Northern Province and the provincial administration was operationalised (this included the need to physically relocate the staff from Trincomalee in the Eastern province to Jaffna in the Northern Province. Thus a complete new administration had to be formed for the Northern Province.

Thus the GIZ-DETA project formally took the decision in 2010 that the implementation of all project measures should be with and through the government system in Northern Sri Lanka and not as initially planned through a national NGO. The methodological approach was revised and adapted to take into account the revised approach.

Figure 2: Step-by-step process for capacity development in GIZ-DETA in Sri Lanka

Step 2: Revised context analysis of government administration in the Northern province

With the new methodological approach having been confirmed, the project proceeded to further assess and contextualise the administrative structure and arrangements for the Northern Province of Sri Lanka. The process for the context analysis involved four steps:

- 1. Review of the existing studies and reports on the National, provincial and local government administrative structure for Northern province;

- 2. Assessment of the main strengths and weaknesses of the different levels and different areas of responsibility especially between the national line departments and the provincial council departments,

- 3. Assessment and joint negotiation with key provincial departments regarding the potential process for implementing the measures to be supported by the GIZ-DETA project in accordance with the respective mandates,

- 4. Determination of constraints that can be realistically addressed by a three year DETA project (compared to structural framework conditions that would need a medium to long-tem development cooperation project to address these issues)

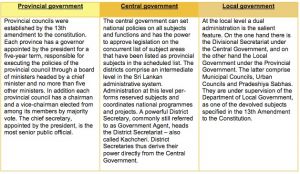

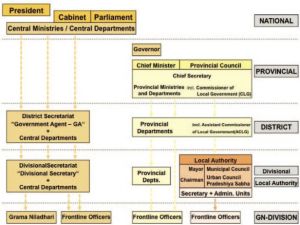

The current administrative and organisation structure which is also applicable for the Northern Province in Sri Lanka is as follows (but not all can be realistically addressed by a three year DETA project):

Sri Lanka has three levels of government: central, provincial and local. Devolution of power is made under three lists as stipulated in the ninth schedule to the 13th amendment to the constitution: List I identifies the functions to be devolved to and carried out by the Provincial Councils, while List II, the reserved list, specifies the functions to be carried out by Central Govenment. List III, the concurrent list, outlines the functions that may be exercised by the centre or the provincial councils following consultation with each other. At the local level a dual administration is the salient feature. On the one hand there is the Divisional Secretariat under the Central Government, and on the other hand the Local Government under the Provincial Government.

The latter comprise Municipal Councils, Urban Councils and Pradeshiya Sabhas. They are under supervision of the Department of Local Government, as one of the devolved subjects specified in the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. This power- sharing initiative was undertaken primarily as an alternative to demands for a separate state by the Tamil political parties and militant separatist groups. It was also seen as a measure to enhance democratic participation by communities and groups in the process of government. Local authorities can be considered as semi-autonomous. The people in them can assess the needs of their area and make certain decisions, depending on the resources they possess.

Table 2: Three-fold government structure with main responsibilities and functions

Figure 3: Government of Sri Lanka administrative government structure

Source: GIZ supported “Performance Improvement Project “ - PIP, Sri Lanka

Main constraints with the current system of government planning and implementation

- The Provincial Government does not include all sectors of government but only those specified in the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution. As a consequence, not all necessary functions that belong to the Provincial Council constitutionally have been devolved (e.g. police and land administration) and some functions which belong to the provincial councils and which were devolved have been re-invested with the central government.

- The District Secretary plays the role of coordinator, linking the activities of central and provincial administrations. Since the GA supervises the Divisional Secretariats, he has a certain influence over other activities as well. In reality, most of the provincial functions and activities at local level are executed and implemented by the Divisional Secretariats. Despite devolution of power to the Provincial Councils and the establishment of elected local councils, the centrally appointed administrative institutions continue to function in the provinces as agencies of the central government The relationship of GA and the province is therefore complicated, since lines of command and responsibilities are not clearly defined. It comes down eventually to personal attitudes of the individuals whether it is a conciliatory or a more conflicting relationship.

- Both the Planning Secretariat and departments complain about the information flow, although in different ways. While the departments complain that the Planning Secretariat burdens their work through frequent but irregular requests for data and information, the Planning Secretariat criticises the poor level of cooperation they receive from the departments.

- Policy-making however, is fragmented between all institutions, which is visible in poor coordination and total lack of strategic planning. Proper development planning is made more complicated.

- Ambiguous division of responsibilities between the centre and the makes it difficult to improve administrative capacity at provincial and local levels.

- Local authorities generally lack capacity for land management and enforcement capacity for development control.

- Coordination of all relevant development actors is inadequate. Thus it is apparent that a multi-headed, hydra-like construct exists especially in the area of physical planning.

- A pivotal problem is the fact that the present planning process is not inclusive. Real participation and decision-making processes do not take place in a manner that guarantees a product that really reflects strategic needs. The population, CBOs, sector departments, and also NGOs are an insufficient part of such a process. There is no adequate channel where the needs and aspirations of these grass roots level bodies (e.g. Community Based Organizations – CBOs - such as women’s societies, rural development societies, farmers’ societies, cooperative societies) can be brought up to the elected Pradeshiya Sabha. For this a mechanism is needed how these community based organizations can be affiliated and effectively linked to the elected local authority. Local level administrations, both local authorities and divisional administration, are incapable of tackling the challenge of coordinating and monitoring activities of NGOs efficiently. The consequence is that the local level administrations cannot present solid development programmes to the NGOs to guide their intervention.

- The selection process of projects is also subject to a political component, since MPs of the area are also involved. They have the power to select special projects to be implemented with their own parliamentary budget (“Decentralised Budget – DCB”). In this way MPs have the power to channel their political influence through the district administration system, undermining to a certain extent the relevance of the local democratic structures, i.e. the local authorities.

- Further the Provincial Council and Local Authorities are strongly dependent on the centre through budgetary allocations, departmental funding and allocations from central MPs and provincial council members.

Additionally to the above-mentioned constraints other specific constraints were identified in the Northern Province as a result of GIZ-DETA SWOT-Analysis tool:

- In October 2006, the North East Provincial administration has been de-merged into two viz: Northern Provincial administration and Eastern Provincial administration.

- Newly formed Northern province required that the administration shift from the former headquarters of the North-Eastern Province of Trincomalee to the new provincial headquarters in Jaffna.

- Staff had to be relocated and the provincial departments had to be (re-)established.

- The necessary personnel and expertise was not always available also due to the results of the decades of conflict

- The Northern Province provincial council is not elected to date, an election is planned for September 2013. There were two fundamental reasons why the central government has shown no urgency in conducting the provincial council election to the Northern Province, (1) security, and (2) politics. Both these factors are linked closely to the history of elections conducted in the North in the post-war period.

- Pradeshiya Sabha were only elected in 2012 in the Northern Province

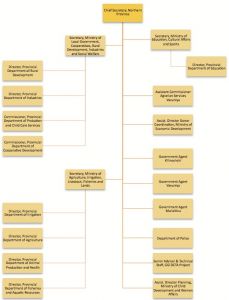

Step 3: Development of GIZ-DETA project steering structure

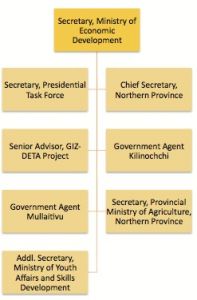

As part of the overall GIZ-DETA capacity development approach, a project steering structure was developed and implemented that was specifically designed to integrate the government administration and the provincial council structure. In view of the national importance of the project, a national steering structure was also developed and implemented.

Figure 4: National Steering Committee of GIZ-DETA Project

At the national level the project is steered by a National Steering Committee (NSC), chaired by the Additional Secretary of the line ministry MED and members include the Secretary of the Presidential Task Force (PTF) and representatives of relevant national ministries, the Chief Secretary of the Northern Province as well as the Government Agents. The NSC provides policy advice and establishes the overall framework of the proposed GIZ-DETA measures to be undertaken in the Northern Province as well as assessing and approving the priority areas of intervention that the project should pursue.

While the national project steering committee for the project was formed in December 2010, it has only met one more time since then, the provincial project coordinating committee (PPCC) has convened every quarter year. The PPCC includes representatives of the line ministry MED, representatives of relevant provincial ministries, the Government Agents of the three selected districts as well as relevant central government structures operating at local level such as the Assistant Commissioner Agrarian Services (ACAD). The Chief Secretary of the Northern Province chairs the PPCC. Main tasks of the PPCC are to ensure effective communication and coordination is undertaken between the various stakeholders. A key function is also to effectively prioritize, finalize and implement proposed project activities.

Figure 5: Provincial Coordinating Committee of GIZ-DETA Project

Step 4: Assessment of capacity development needs

For the implementation of the GIZ-DETA project working with and through the government and provincial council system in Northern Sri Lanka was not only designed to achieve an impact with regard to the development measures but also to achieve an impact in capacitating the provincial council system. The objectives that were being pursued included:

- Developing and strengthening the planning, management, implementation and monitoring capabilities of the various different departments within the provincial council

- Re-connecting and supporting the departments in gaining the trust of the population in the selected districts with the newly developed capabilities of the departments

- Developing and strengthening state-society relations in a province that had been affected by decades of conflict and where a fledgling administration had been institutionalised but that lacked substantial capabilities and capacities.

Step 5: Decision on capacity development methodological approach: On-the-job-training

One of the main instruments used for capacity development by the GIZ-DETA project was on-the-job training. This seeks to impart skills and knowledge for the technical and administrative staff of the government line ministries and provincial departments as they work within the actual process of assessing, planning, implementing and monitoring the GIZ-DETA supported project measures.

On-the-job-training was divided between providing (formal) structured and unstructured (informal) methods which involved providing technical support through the project advisors to the government and provincial department staff. The formal structure training included supporting government technical and administrative to attend national and international courses on a variety of different topics. Informal training consisted of regular provision of technical and administrative know-how through the project specialists. The combination of both approaches was seen as the most cost-effective and efficient way of providing capacity development in the short space of time available for implementing the GIZ-DETA project (three years).

An effective way of promoting on-the-job training was to utilise the Local Subsidy Contract tool of the GIZ. The local subsidy contract allows the GIZ-DETA to make a contract with any partner organisation, including government and provincial councils departments. The contract stipulates the objectives and activities that will be implemented by the partner organisation and will also define the financing procedures. The partner organisation has the full responsibility for implementing the local subsidy contract. A major part of the local subsidy contract involves improving the planning, management, implementation monitoring and reporting skills of the partner organisation. These improved skills are likely to also benefit the partner organisation above and beyond the implementation of the local subsidy contract. The GIZ-DETA team continues to assist in administering the local subsidy and they are ultimately responsible for the proper use of the funds by the recipient. Furthermore, the GIZ-DETA team assumes an advisory and monitoring role with regard to compliance with regulations on the procurement of materials and equipment and the purchase of appraiser, consulting and construction services.

The main capacity development measures that were trained through the use of local subsidy contracts and other on-the-job-training included:

- Project proposal writing

- Project assessment and feasibility

- Project selection

- Project planning

- Project implementation, including operation planning

- Financial and budgetary planning, monitoring and accounting

- Monitoring and evaluation

- Reporting and documentation

- Special technical skills such as building plans, development of training modules etc.

This means that the project focused mostly on addressing performance/capacity and accountability/legitimacy constraints but very little can be done in the short period of time of realistically addressing framework/authority constraints.

Step 6: Selection of priority areas of intervention

While the initial selection of the territorial area where the project should work was highlighted in the original project commission (it was the result of the initial project assessment) the exact details of which sub-districts or villages to work in were left open. Thus, one of the first steps that the project needed to clarify was the exact area where the project should be active in.

This selection process was undertaken by the Government Agents in close collaboration with the central government, the concentration was to be areas where all recently re-settled people from the refugee camps were to be found and/or where very specific problems related to the resettlement programme existed. The selection of thematic areas of concentration of the project was defined in the project commission that was based upon the given context and planning documents of the Sri Lanka government (including the above mentioned ‘Uthuru Wasanthaya’ or Northern Spring plan.

While all thematic areas were re-confirmed by the national and local level at the start of the project the aspect of psycho-social counselling had to be taken out of the project outputs.

Photo 4: Enhancing agricultural libelihoods -paddy harvesting - (source: GIZ-DETA)

Photo 5: Improving access to education - rehabilitation school water and sanitation facilities

(source: GIZ-DETA)

Step 7: Joint planning and implementation process

Step 7.1 Designing of project proposals

During the designing process of the project measures the applicants were the government departments who bought in ideas jointly developed with the affected communities. The application process also helped to strengthen and develop the skills to design proposals, plan activities, drawings, develop estimates and detailed budgets. Projects are to be identified by the final beneficiaries. Selection of the project measures was a joint process between beneficiaries and local institutions to ensure consistency with the overall development planning. As a general principle the project-proposing local institution was required to make a funding contribution towards the financing of the project (possibly with an exemption for very poor communities). The contribution was in cash, kind (materials, land) or labour.

Step 7.2 Project applications

The applicant presented the detailed project proposal on the basis of a format that had been designed and elaborated between the GIZ-DETA project and the government administration by the Project Progress Coordinating Committee and Chief Secretariats Office of the Northern Province in Jaffna. Three proposal formats were jointly designed and the used for the process: project proposal, proposal for food-for work measures and proposal format for food for training.

Step 7.3 Feasibility study and selection

Every project proposal was registered and was given a reference number. GIZ-DETA’s technical team then undertook a pre-screening of the submitted project proposals and also undertook site inspections. In some cases the GIZ-DETA also supported the applicant in revising and improving the quality of the proposals (this is to be seen as part of the on-the-job training). The initial assessment of the projects undertaken by the GIZ-DETA team was done according to the following jointly agreed upon criteria:

- The project is designed to benefit returnees in the selected areas

- The project is consistent with national and sector priorities.

- The project is in the scope of GIZ-DETA Project components and agreed priority areas of intervention.

- The implementing institution can effectively deliver the intended benefits to the target groups.

- The estimated budget, drawings are appropriate for the type of project proposed.

- The maintenance costs implied by the project can be effectively met (sustainability).

- Beneficiary communities are involved in project design, implementation and monitoring.

- Beneficiary communities can make a contribution (in cash or kind) towards project costs.

Project proposals, which are pre-screened and approved by GIZ-DETA’s technical team, then underwent a second assessment and evaluation round. This was undertaken by the PPCC who reviewed the pre-screened project proposals for feasibility, compliance and they also granted the final approval. Local institutions were then informed about acceptance or rejection of their proposed activities. Projects, that were not within the overall scope of GIZ-DETA were forwarded to other donor agencies for consideration.

Step 7.4 Contracting

After the project approval, a local subsidy contract was prepared jointly by the GIZ-DETA project and the GIZ Country Office in which the applicant was commissioned to take the responsibility for the implementation and enter a local subsidy contract. Different types of contracts were drawn up depending on whether there was a financial contribution involved from the cooperating partner, whether the contracting amount exceeded €50.000 or whether the contract involved a building / construction component.

The latter requires the involvement and approval of the GIZ-HQ Construction Division whose approval has to be documented in writing in the project file using the standard form “Approval to implement a construction measure by the Construction Division”. The contract includes all the rights and obligations of the contracting partners. The Local Subsidy Contracts was then signed by the respective officials of GIZ-DETA Project, GIZ Country Office and the respective Head of the Department with the countersignature of the respective Secretary. A copy of the signed local subsidy contract was then sent to the Chief secretary, DCS, Planning and Director, Department of Donor Coordination, MED.

Step 7.5 Provision of funds and financial processing

Funding was provided directly to the contracting partner. They were obliged to fulfil the financial and reporting obligations as per the contract. If necessary a separate bank account had to be opened.

All payments to be contracting partner were released from GIZ-DETA accounts department after signing the contract. The funds were released in number of instalments, depending on the size of the contract. The first instalment was provided after signing the contract (for this an advance payment sheet was used), later instalments were paid after submission of respective financial monitoring reports (use of a “settlement sheet”), and the last instalment was provided after the project was completed and satisfactorily evaluated.

The original invoices of all goods and services had to be submitted to GIZ-DETA with a settlement voucher. The contracting partner got copies of the vouchers after stamping “paid”. All vouchers were duly checked by technical and finance team of GIZ-DETA and each voucher was then stamped as being “correct” and signed by both responsible technical and accounting staff. All costs regarding VAT and Contingencies are not covered by the contract and needed to be excluded from the budgets.

Figure 6: Flow diagram of financial processing of local subsidy contracts

Step 7.6 Project implementation

The GIZ-DETA actively supported the partner organizations throughout the implementation process. The GIZ-DETA technical team technical team regularly monitored the implementation process. This included providing on-the-job training, advisory services, jointly assessing the outcomes, outputs as well as the initial impact the project is having on the beneficiary level. When unforeseen event impacted upon the implementation of the partner project, both the GIZ-DETA team and the implementing partner reassessed the context and revised and adapted the implementation plan as needed. The project also encouraged the implementing partner organization to report on progress of the implementation of the local subsidy contract.

For the implementation of the project by the partner organisation the following steps were undertaken:

Development of a plan of operations: On the basis of the agreed objectives defined in the local subsidy contract, the partners further elaborated a plan of operation. The plan of operation defined the detailed steps how the project was going to be implemented

Beneficiary selection: The complex context in the Northern Province of Sri Lanka required that all project activities are in-line with the do-no-harm principles and that they are all conflict sensitive. The first step towards this included in the implementation of a proper beneficiary selection mechanisms. The results of this were then also fed into the process of adapting the project to ensure that the needs of the most vulnerable were considered. The GIZ-DETA project established a committee for selecting the beneficiaries who benefitted from reintegration and rehabilitation activities. Transparent beneficiary lists were developed using a set of criteria. In each village the list of beneficiaries was also displayed in public. The main criteria was that the beneficiary should be a returnee to the selected project areas and in addition the following other criteria were applied:

- Permanently resettled in the respective villages.

- Priority for woman headed/widowed families.

- Only one member in a family was eligible to receive one project measure (e.g. home-garden package/poultry unit/fishery gear).

- Families having the necessary capacity and interest.

- Families should not have received similar support from any other organizations after re-settlement.

Procurement of materials, equipment and services: The implementing partners who needed to order supplies or make services contracts they needed to comply with the local subsidy rules and regulations. For this process the GIZ-DETA staff provided continuous technical and administrative support. Once all rules and regulations for procurement had been followed and the contract awarded then the award or order placement decision was documented in a procurement file.

Step 7.7 Project monitoring and reporting

During the project implementation there was close joint monitoring by GIZ-DETA and the partner organization. This consisted or regular joint field and site visits, discussion with beneficiaries by the GIZ-DETA and the partner organization staff. During these visits they provided further on-the-job training and advisory services and addressed and jointly resolved any constraints that arose during the implementation process. The GIZ-DETA team also compiled an overall activity sheet to document all the different activities and these presented and discussed within the GIZ-DETA team on a weekly basis. The following is a typical example of the results chain monitoring for a local subsidy contract.

Figure 7: Example of typical results chain for local subsidy contract

The monitoring of the results of the implemented measures proved quite difficult when measuring both quantitative and qualitative factors. The GIZ-DETA used various different tools to assess the outcomes, including field data collection, surveys, questionnaires, open forum discussions, etc. The results of the monitoring were then documented and reported.

At the quarterly meetings of the PPCC the project presented regular progress reports. These were then discussed with the PPCC members and the project received further guidance and ideas how to proceed in the next quarter. Important was that the presentation of the results was done by the partner organizations at the PPCC and not by the GIZ-DETA project. This helped create a common understanding of the whole process and allowed for better monitoring of the implementation of activities.

The GIZ-DETA’s internal monitoring system was also linked to the Government of Sri Lanka monitoring tool. This tool had been developed through a consultative process as a primary monitoring tool for all stakeholders and it is called “3W - Who does what where. The tool tracked the progress of the humanitarian and early recovery efforts that supported the re-establishment of services and livelihood access across the Northern region. 3W is a global tool used to coordinate information during emergencies.

In Sri Lanka the 3W tool was initially used by OCHA following the Asian Tsunami in 2004 to provide operational support in coordination of humanitarian assistance. Thereafter the 3W tool was maintained by OCHA to collect data from agencies operational in Sri Lanka and has now been integrated into the Sri Lanka monitoring system for Northern province of Sri Lanka

Final reporting and accounting of the local subsidy measure: After a LSC contract measure has been completed the partner organizations submits a final report and then the final payment is made. The GIZ-DETA team supported the partner organizations in conducting the final monitoring of the project and in ensuring that the respective beneficiaries also adhere to the aspects of sustainability of the project (especially the issue of maintenance). The final report marks the end of the local subsidy contract and also the end of the direct assistance provided by the GIZ-DETA project to the partner organization.

Contract monitoring and auditing: When a project implements numerous local subsidy contracts an overview of the implementation process had to be maintained. This process includes contract monitoring. Using an ordinary excel sheet could be the easiest way of monitoring ongoing contracts and payment details. On the other hand the overall financial monitoring for the project management was done using a pre-designed MS-ACCESS database, which was developed to plan and monitor ongoing project activities.

Auditing the use of funds for their intended purpose remained the responsibility of the GIZ-DETA staff responsible for the contract and cooperation. Overall auditing was undertaken for the project both by external auditors as well as auditors from the GIZ Country office.

Photo 6: Establishing business support centres (source: GIZ-DETA)

Step 7.8 Overall reporting

The GIZ-DETA project compiled regular annual project progress reports for the donor ministry in Germany (BMZ). The report provided a transparent information basis on project/programme status that can was empirically verified. The reports contributed towards assessing the quality of the project/programme. The progress report provided information on the status of results and objectives achieved, and documented the most important events occurring and decisions taken during the reporting period. The progress report also served as a tool for enabling BMZ to perform its development-policy and strategic steering tasks for Sri Lanka as whole.

Step 8: Key lessons-learnt

A final step in the GIZ-DETA project process was a lessons-learnt exercise. The exercise forms part of an overall evaluation process which was designed as part of institutional learning and meeting accountability obligations towards the client and the general public (the results of the lessons-learnt have been integrated into this application example).

The lessons-learnt has revealed the following:

- Capacitating and implementing the GIZ-DETA project objectives with and through the government institutions worked effectively in the context of the Northern province of Sri Lanka;

- The approach also works for relatively short project periods of only three years which is normal for GIZ-DETA projects;

- The strategy of providing capacity development through a combination of on-the-job training and advisory services to the government institutions (who then in turn capacitated the beneficiaries) also worked out successfully;

- The strategy of using local subsidy contracts as a tool for achieving the project outputs and as a key instrument for capacitating the government institutions also functioned well;

- In the three year implementation period of the project 239 project proposals were received, 65 were approved of which then 54 local subsidy contracts were completed. In total the project benefitted (via the government institutions) a total of 39.226 beneficiaries (out of whom 14.900 were women) as well as 23,318 school children (where 208 schools were rehabilitated) and 6.900 persons benefitted from the psycho-social counseling.

Photo 7: Results of the good productive cooperation (source: GIZ-DETA)

|