Establishment of a Social Security and Maintenance Fund (SSMF)

Constructing a road in mountainous terrain is a challenging task and although ILRA made considerable efforts to ensure the workers’ safety (training, high-quality tools), accidents could not be totally prevented. To prepare for such mishaps, the project established a Social Security and Maintenance Fund (SSMF). To build up the fund, ILRA deposited 1 Nepalese Rupee (1 NPR ≈ 0.9 EUR) for each kilogramme of rice distributed to the workers on a special bank account. This money was used to treat injured workers and to compensate the families of the victims of the few fatal accidents which occurred in Bajhang (2 casualties) and Baitadi (1 casualty). This group insurance gave up to 200,000 NPR to the family of a worker who had a fatal accident.

The funds were managed by the Road Federation Committee in collaboration with the district coordinator, who during the project implementation was a signatory of the SSMF. The Road Federation Committee set up clear conditions for the use of its resources. As the name indicated, the fund had a dual function: After the road was finished the remaining resources formed the financial basis for future maintenance works (see Section 4 Maintenance).

Construction Work According to the “Green Road Approach”

The Rural Road Construction Strategy followed the provisions of the “Green Road Approach” which was developed by German and Swiss development cooperation in the late 1970s. A “green road” is a fair-weather road for light vehicles only, which is adapted to local environmental conditions and can easily be maintained by local road users. To generate a maximum of local employment opportunities labour-intensive road construction methods (mainly manual work) were adopted rather than machine-based technologies (e.g. excavators). Special attention was paid to minimising environmental damage. Every year an Environment Measure Plan was conducted to consider which construction problems could occur during that year.

Photo 5: Manual construction techniques used simple tools which were locally available

Worker groups were equipped with hammers, chisels, crowbars, and shovels (see Photo 5). Most of these simple tools could be procured locally. The workers were familiar with their handling. They were repaired by local blacksmiths (see Photo 6), which provided additional employment opportunities on the construction sites.

Photo 6: Local blacksmiths earned additional income by repairing construction tools

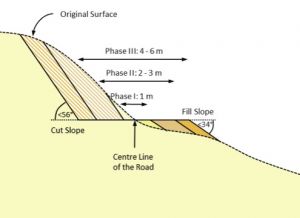

In Bajhang and Baitadi, construction works started in December 2009 and January 2010 respectively. Following the provisions of the Green Road Approach, construction was conducted in three phases which were interrupted by two monsoon periods during which construction was stopped (see Figure 1). The road was allowed to settle down over the monsoon period and slope stability was increased by natural compaction processes. This approach produced less excavation material at any one time, which made disposal management much easier. However, in some sections the project team decided to deviate from this general rule: Where agricultural fields on soft soil were affected, the road was constructed in one go in the third construction phase. Otherwise the landowners would have had to protect the remaining parts of their fields with temporary stone walls after each extension phase.

Figure 1: Phased construction allows for natural compaction and increases slope stability

Mass-balancing was of major importance during each construction phase. While conventional road construction approaches often apply box-cutting (i.e. the road is entirely cut into the slope), WGs in Baitadi and Bajhang used a cut-and-fill technique. The centre line of the road was located near the original slope surface and the road was extended by cutting the slope on one side of this line and depositing the material on the other (see Figure 1). Understandably, WGs tended to start working on the soil and soft rock parts within their respective section. But the project team encouraged WGs to start with hard rock parts. This was because otherwise it would have been very difficult to finish the road within a short project time period. While soil and soft rock (e.g. slate) were excavated manually by shovelling, hammering and chiselling, the beneficiaries used the traditional and effective method of “heating and breaking” (see Photo 7) for harder rocks like limestone and dolomite. Only on rare occasions the project team decided to hire an excavator for sections of very hard rock.

Photo 7: Hard rock sections are heated by a fire and become brittle after cooling down over night

Excavated material was primarily used to extend the road on the fill slope side. Bigger stones were stockpiled so that they could be reused for stone structures (e.g. gabion and masonry walls) later on (see Photo 8). If possible, any excess material was deposited in a controlled manner within a buffer of 50 to 100 m from the location where it had been excavated. Local supervisors and project technicians took care that no important drainage lines were blocked and no material was deposited on agricultural land. In cases where this could not be prevented, WGs immediately removed the material so that food production was not hampered.

Photo 8: Excavated stones are stored and reused to construct protective structures

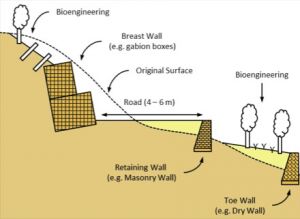

Several stone structures were built to protect the road and prevent landslides and erosion (see Figure 2). Wherever material was deposited on slopes steeper than 30° it was protected by toe walls. These walls are especially important to protect the foundation of uphill gabion walls from erosion. Other protection structures were retaining walls, stabilising the valley side of the road, and breast walls, supporting the remaining cut slope. In soft soil and rock, walls of gabion boxes were preferred over masonry walls, because they are very flexible and stable. They consist of stacked boxes of wire mesh which are filled with stones by the workers. The stability of these walls highly depends on a proper stone packing and a solid foundation (see Photo 9). WGs were trained in both areas at the beginning of the project.

Photo 9: Packing the wire mesh properly is paramount for the stability of walls of gabion boxes

In harder rock sections gabion walls were replaced by masonry walls. Their stability depends to a large extent on proper cement, which itself is dependent on good quality sand. In mountainous areas like Baitadi and Bajhang districts such material is hard to get so that masonry walls were not used often. In cases where only small volumes of material had to be retained (e.g. toe wall), dry walls were used. These consist of stones which are not joined by cement but kept together by their own weight. In both project areas it was not always possible to prevent that the road crossed slope sections which were prone to landslides. In these areas catch drains were built above the sliding zone so that rainwater was diverted away from the slide. In order to prevent erosion damage, existing gullies were blocked by check dams which slow down the rainwater runoff and decrease its erosive power.

Figure 2: A combination of stone structures and bio-engineering techniques was used to protect the road

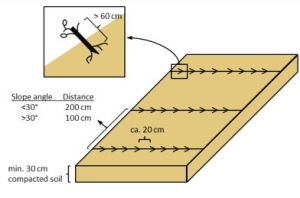

These prevention structures were complemented by bio-engineering measures. They make use of living plants which reinforce the slope surface through their roots and help control soil erosion and shallow landslides. A combination of brush layering (see Figure 3) and planting of grass and trees proved to be very effective. Only local plants which were adapted to local soil and water conditions were chosen. Beneficiaries who are familiar with the local environment gave useful hints. In some locations additional advantages could be gained by using plants which had additional value as fodder trees. In other areas however, it was decided to use plants which are inedible for livestock, so that grazing on instable slopes was prevented. Some local farmers took over the task of growing the saplings in nurseries. The planting of bushes and trees was done during the monsoon period when all other work was stopped and environmental conditions were best for the saplings to take root.

The World Food Programme (WFP) hired consultants from the Scott Wilson consultancy to monitor the construction sites at regular intervals, so that their external feedback gave additional input for the quality control.

Figure 3: Locally obtained green cuttings were used for brush layering to stabilise slopes

Payment Procedures

The road construction schemes in Bajhang and Baitadi districts were integrated into a food- and cash-for-work framework. Workers were paid with a combination of cash, rice and pulses and payment was based on accomplished outputs, not on a fixed daily rate. This mode of payment provides an incentive for the workers. It accelerates the construction process and rewards dedicated groups.

At regular intervals ILRA field technicians estimated the construction progress of each WG. The accomplished output of the whole group was entered into a work valuation sheet. The form included different types of work (excavation, stone transportation, filling gabion boxes with stones) and different soil/rock types (soil, ordinary rock, medium rock and hard rock) which were evaluated differently. Disadvantages for groups working on hard rock compared to those working on soft soil were thus avoided. Having evaluated the work progress the technicians produced one bill for each WG with the total amount of money, rice and pulses earned by the group and handed it over to the respective UCs. The UCs made a request to WFP for the payments. Then ILRA’s district coordinators gave their consent and WFP released the cheques in presence of ILRA staff in a publicly open event. The UCs handed over the payment (money and coupons) to WGs. The coupons entitled WGs to collect rice and pulses at one of the project warehouses. WGs could decide whether to transport the food themselves or to commission its transportation (mules, porters). Finally, the amount earned was split among the members according to the attendance records. The remuneration for a “daily work norm” was 2 kg of rice, 250 g of pulses and 85 NPR. However, according to their dedication groups could earn more or less than this amount per day.

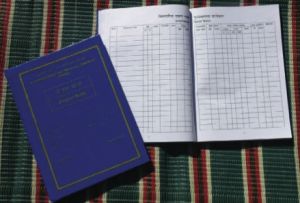

To ensure transparency the amount of all labour payments were made public and monitored by social mobilisers. To further increase transparency all expenses were meticulously written down in a project book which was kept at the road side by the UCs in order to keep a full record. These books were consulted during public audits (see Photo 10).

Photo 10: Publicly available project books guaranteed transparency and accountability

Settling Land Conflicts

Voluntary land contribution by future road users without compensation by the project is one of the core principles of the Rural Road Construction Strategy. The contribution is compensated indirectly through the increase in value of the remaining land due to road access. This approach increases the feeling of ownership for the road among the landowners along its corridor and reduces construction costs considerably. Therefore at the very beginning of the project beneficiaries in the project areas had been requested to formally agree to this basic rule. At that early stage this agreement was not disputed at all. Once the construction work started, some of the landowners changed their mind and opposed works on their land. Land conflicts usually arose where agricultural land was affected or where existing infrastructure was in danger (see Photo 11). Reluctance to contribute land by just one landowner could jeopardize the whole project. Therefore, settling such conflicts to mutual satisfaction was of the utmost importance.

Photo 11: Land conflicts arose especially in areas where existing infrastructure was affected by the road construction

Resolving land-related conflicts and persuading worried landowners of the advantages of the new road was the responsibility of the UCs, the Road Federation Committees and the government authorities. The ILRA project team only supported the conciliation process by facilitating meetings and mediating between different interests. In addition social mobilisers supported UCs in defining clear procedures for developing solutions to conflicts. These were always based on consensus, so that the issues were settled irrevocably. Solutions sometimes included indirect compensation through side-project activities (e.g. provision of a green house, rehabilitation of irrigation infrastructure).

|